Lt. Col Sir Andrew Leith-Hay of Rannes and Leith Hall and Mary Margaret Clark

Sir ANDREW LEITH-HAY (b.17 Feb. 1785– d. 13 Oct 1862), writer on architecture and military history, was born at Aberdeen on 17 Feb. 1785. His father, Alexander Leith Hay, (1758–1838), formerly Alexander Leith, was appointed a lieutenant in the 7th dragoons immediately on his birth, captain 1768, and colonel in the army 1794. Upon the death of Andrew Hay in 1789 he inherited the estate of Rannes, Aberdeenshire, and assumed the additional surname of Hay, being descended from that family through his paternal grandmother. On 1 Oct. in the same year he was gazettedcolonel of a regiment raised by himself and called by his name. He was promoted to be major-general 1796, lieutenant-general 1803, full general 1838, and died in August 1838 (Gent. Mag. 1838, ii. 321). He married in 1784 Mary, daughter of Charles Forbes of Ballogie; she died in 1824. The eldest son, Andrew Leith, entered the army as an ensign in the 72nd foot on 8 Jan. 1806, went to the Peninsula in 1808 as aide-de-camp to his uncle, General Sir James Leith, and served through the war until 1814. He was much employed in gaining intelligence, and was present at many of the actions from Corunna to the storming of San Sebastian. Wherever he went he made sketches, and in 1831 worked up up these materials into two volumes, entitled ‘A Narrative of the Peninsula War.’ On General Leith being appointed to the governorship of Barbados in 1816, his nephew accompanied him, and discharged the duties of military secretary and also those of assistant quartermaster-general and adjutant-general. As captain in the 2nd foot he served from 21 Nov. 1817 to 30 Sept. 1819, when he was placed on half-pay. He had previously been named a knight commander of the order of Charles III of Spain, and a member of the Legion of Honour.

Sir ANDREW LEITH-HAY (b.17 Feb. 1785– d. 13 Oct 1862), writer on architecture and military history, was born at Aberdeen on 17 Feb. 1785. His father, Alexander Leith Hay, (1758–1838), formerly Alexander Leith, was appointed a lieutenant in the 7th dragoons immediately on his birth, captain 1768, and colonel in the army 1794. Upon the death of Andrew Hay in 1789 he inherited the estate of Rannes, Aberdeenshire, and assumed the additional surname of Hay, being descended from that family through his paternal grandmother. On 1 Oct. in the same year he was gazettedcolonel of a regiment raised by himself and called by his name. He was promoted to be major-general 1796, lieutenant-general 1803, full general 1838, and died in August 1838 (Gent. Mag. 1838, ii. 321). He married in 1784 Mary, daughter of Charles Forbes of Ballogie; she died in 1824. The eldest son, Andrew Leith, entered the army as an ensign in the 72nd foot on 8 Jan. 1806, went to the Peninsula in 1808 as aide-de-camp to his uncle, General Sir James Leith, and served through the war until 1814. He was much employed in gaining intelligence, and was present at many of the actions from Corunna to the storming of San Sebastian. Wherever he went he made sketches, and in 1831 worked up up these materials into two volumes, entitled ‘A Narrative of the Peninsula War.’ On General Leith being appointed to the governorship of Barbados in 1816, his nephew accompanied him, and discharged the duties of military secretary and also those of assistant quartermaster-general and adjutant-general. As captain in the 2nd foot he served from 21 Nov. 1817 to 30 Sept. 1819, when he was placed on half-pay. He had previously been named a knight commander of the order of Charles III of Spain, and a member of the Legion of Honour.

Having retired from the army he turned his attention to politics, took part in the agitation preceding the passing of the Reform Bill, and became member for the Elgin Burghs on 29 Dec. 1832. Shortly after entering parliament his readiness as a speaker and his acquaintance with military affairs attracted the notice of Lord Melbourne, who conferred on him the lucrative appointment of clerk of the ordnance on 19 June 1834, and also made him a knight of Hanover. On 6 Feb. 1838, on being appointed to the governorship of Bermuda, he resigned his seat in parliament. Circumstances, however, arose which prevented him from going to Bermuda, and on 7 July 1841 he was again elected for the Elgin burghs, and continued to sit till 23 July 1847. At the election in the following month he was displaced, nor was he successful when he contested the city of Aberdeen on 10 July 1852. To county matters he paid much attention, more especially to the affairs of the county of Aberdeen. His most interesting and useful book, entitled ‘The Castellated Architecture of Aberdeenshire,’ appeared in 1849. The work consists of lithographs of the principal baronial residences in the county, all from sketches by himself; the letterpress, which contains a great amount of information, being also from his pen. He died at Leith Hall, Aberdeenshire, on 13 Oct. 1862. His wife, whom he married in 1816, was Mary Margaret, daughter of William Clark of Buckland House, Devonshire; she died on 28 May 1859. His eldest son, Colonel Leith Hay, C.B., is well known by his service in the Crimea and India. (A Brisbane Courier article from 1862 also relates the above with more details. Andrew_Leith_Hay_Obituary_Courier_Bris.

[Times, 17 Oct. 1862, p. 7; Gent. Mag. 1863, i. 112–13; Men of the Time, 1862, p. 371.]

Siege of San Sebastian Spain with Liet General James Leith at the lower left corner. Image credits to the National Trust Scotland. The siege image shows where the great breach and lesser breach are located as per the image to the left where the allied troops pour into the breaches under heavy fire and casualties. Andrew Leith-Hay arrived at San Sebastian one day after the storming.

In the family book Marion Lochead describes Sir Andrew as the most versatile of all the Lairds of Leith Hall. This may be true in terms of all the volume of information available on him and his own prolific work. After all he published three books. Firstly, his uncle’s Sir James Leith’s memoir. Secondly, the detailed Peninsular war narrative and thirdly, his Castellated Architecture of Aberdeenshire. The sketches and lithographs in the latter two prove he was a gifted artist as well as a writer. Andrew’s position as an intelligence officer and A.D.C to his uncle James Leith also offered him largely a view of the major battles of the war as that of an observer rather than one who was in the thick of battle. Most of the detailed descriptions could only be possible from a vantage point overlooking the whole melee and for this reason his battle scenes of the major engagements of the war are often described in set piece detail.

This does not mean he did not partake in front line duty. Clearly his account on his personal experience shows that he did and was also wounded. The ordeal and lot of the common soldier is also given some place in his narrative, and in later life he would campaign for the recognition of veterans by passing the Peninsular medal. It has to be remembered that Andrew wrote his work while most of the events were fresh in mind and his superior officers were mostly alive in 1831 only 15 or so years after the events and for this reason his work is rarely critical of any of his commanding officers. His narrative is in stark contrast to his 3rd son’s James Leith Hay’s future father-in-law Col Charles Gray’s personal diary of the Peninsular campaign, which offers the portrait of the life of a junior British officer in the Rifle Brigade. For the common soldier this diary only published in 2009 would give a more accurate account of the gruesome war that gripped Spain and Portugal at that time and his prior service in India.

Andrew’s financial difficulties past his father’s death in 1838 also affected his latter life and political career. The Lairds of Leith Hall had been to some extent profligate spenders and especially so Andrew’s father General Alexander Leith Hay, whose military commissions were mostly bought during his life-time rather than achieved out of promotion in the field and battle as Andrew’s father did not partake in any active service in any campaign. Alexander’s expansion of the Hall until 1897 was also a costly endeavour and his inheritance received from his great uncle Andrew Hay was largely spent rather than servicing the debts inherited from his ancestors.

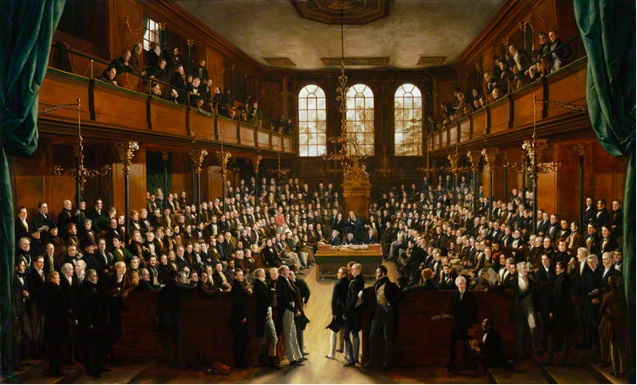

House of Commons 1833 – Sir George Hayter (c) National Portrait Gallery, London

Sir Andrew was also never able to take up his post as Governor of Bermuda due to the financial difficulties he had inherited from his father and the anomalous trust deed that placed a heavy burden on the estate and had contributed to the spending largesse of the Leith Hay Lairds as it in effect gave access to easy credit on the basis of the estate’s holdings being able to service it. Andrew’s own spending habits no doubt made the situation worse and the ballooning of the debt during the course of his business and political career further placed him or rather his estate in a difficult position. The bailiffs collecting the family’s and even servant’s personal items received mention in the London papers and were discussed in more depth in the family book. The difficulties are later evident as the estate (lands of the Hall) were sequestered in 1846 and placed under control of a trust in Edinburgh, whereby the income from the estate was used to pay off his debts. Some info on Andrew’s financial struggles can be obtained here (click here for supreme court case andrew_supreme_court or court_of_session)

This financial situation continued three years past Andrew’s passing in 1862 and thus it took 20 years to disentangle the complex financial set up that had been established in the past. The development of the Hall did not begin again until 1868. Andrew was the only Laird who did not actually add to the Hall himself during his lifetime, although he did add the loch which of course still features prominently today at the Leith Hall Gardens and Estate. Between 1797 to the mid 1860’s the people living in the estate would not really have seen their living conditions improve greatly, since fairly little was returned to the community and the experience of the agrarian crises of the 1840s to early 50’s, which also saw Sir Andrew’s younger sons departure from Scotland due to the changes affecting the family at that time.

The parishes owned by the Leith family would have, however, benefitted from the development of the agricultural revolution that began taking place and resulted in a change in farming practices as well as infrastructural improvements which opened access for agrarian commodities to the towns and ports close by. The next two Lairds would also pay more attention to local matters and people rather than world affairs. The latter lives of Andrew’s eldest son Sebastian and his nephew Charles’ time as Laird’s of the Hall were devoted to local matters of the estate . A history from the Edinburgh Gazette can be obtained on the link ( sequestered) on the development and final resolution under Andrew’s oldest son Sebastian.

As an end note, in the modern work on his career and times in Spain, McGrigor, in Wellingoton’s Spies, describes Andrew as somewhat pompous. This maybe partially a correct analysis. However, the times in which he lived and his own life experience should be taken into account. From his life experience from Spain’s gruesome war against Napoleon, to the tropics of the West Indies, Andrew, was an officer and a politician who rose to prominence during the birth of Britain’s empire at the beginning of its century of dominance of the world post 1815. With first hand knowledge and his own participation in these events as well as his own access the the prominent people of his time justifiably mark him as the most versatile of all the Lairds. No other equalled him in productive historical works. In this perhaps, his uncle Liet General James Leith, through his long mentorship proved the spark. Andrew was obviously greatly influenced by his uncle and this can perhaps best be seen in his anonymous biographical work two years after his passing in 1818.

The below 1862 obituary on Sir Andrew provides another version on his life. In the family book some 100 years afterwards some of Andrew’s shortcomings obviously receive more space than the glowing account at the time of his passing or in the literature of his time where a positive write up would have of course been the expected norm. His financial weaknesses obviously being highlighted as one of his vices in the latter day account. Besides his London residence being emptied of items to even his servants quarters owing to his debts at the time, there is, however, very little other material of substance or gossip that would have scandalised him further at the time. He appears throughout his life to have been a devoted husband to his wife Mary and father to his children. His marriage appeared a happy one and it is hard to find any hint of a Wellingtonesque ladies man or beau in him during his heyday.

Andrew’s financial weaknesses also make him appear more human and therefore a much more interesting subject to delve into. He may have been rightly criticised for being an infernal aristocrat or toff during his day by his detractors. He was certainly proud of his heritage which also gave him a leg up in life yet this is not to say his birthright provided him an easy path. He was a talented individual, which is attested by his soldiering career, literary work and latter relative political longevity as the member for the Elgin Burghs. In hindsight his debts were his undoing in 1838 and it is in this year he was also briefly locked up due to his insolvency and on being bailed out he made a brief escape for the continent for some respite. Andrew was also saved by the fortunate circumstance of being recipient of the inheritance of his estate and this being able to sustain him through the long-term owing to his luck of winning the Y-DNA lottery at the time of his birth.

Obituary from the Elgin Courant Fri, Oct 17, 1862.

The Late Sir Andrew Leith-Hay of Rannes

All our old readers in the district shoe have taken an interest in political affairs for the past thirty years will be sorry to hear that Sir Andrew Leith- Hay is no more. On Tuesday week, he was at a county meeting held in Aberdeen, in the enjoyment of his usual health and even on Monday last he was out on his pony after mid-day, and was dead before four o’clock on the same afternoon, the cause of his sudden death it is believed, being constipation of the bowels.

An interesting volume might be written on the life of Sir Andrew Leith Hay, who was a gallant soldier, and fought many battles in his youth, and whose name, after the year 1832, became a household word in this and many adjacent counties. The deceased gentleman was born in Aberdeen in 1785, and has consequently died at the advanced age of seventy-seven. He was the son of General Alexander Leith-Hay of Rannes, and could boast of an ancient pedigree, down even, it is said, to the reign of King Robert Bruce. Being thus the son of a soldier, and being himself of an enterprising spirit, Leith-Hay, the subject of our memoir, entered the army in early life, and was appointed aide-de-camp to General Leith, his uncle, in 1808, when he was twenty-three years of age. This was at the beginning of the Peninsular war, and the young soldier had to direct his steps to Spain, and live in camps with the British army, then beginning to drive the French out of that country.

Nature seemed to have intended Leith Hay for an aide-de-camp ; young, daring, quick in discernment, and prompt in action, he discharged his duties in a manner at once honourable to himself, and most advantageously to his country. While doing this, he noted down and deeply impressed upon his memory the sciences of battle -fields, meanwhile sketching the romantic scenery of Spain ; and in 1832 he published two volumes of the Peninsular war, pleasantly written, and containing much interesting information. He was present at the terrible retreat of Sir John Moore on Corunna, when the British army marched day after day, ankle deep in mud, until the last the fearful embarkation took place, which left so many gallant British soldiers dead upon the shore, and among the rest their gallant General, one of the very best that Britain had in the war, and over whose grave the generous Soult raised a monument. Leith Hay was also at the sanguinary battle of Talavera, also at Busaco, famous in song, Salamanca, Vittoria, and San Sebastian. While in the discharge of his duty near Toledo he was taken prisoner and brought before General Soult, who offered a soldiers liberty in such circumstances on his giving his parole of honour. This he refused to do, which was rather unaccountable conduct, and the consequence was, as might have been expected, that he was rather harshly treated.

By an exchange of prisoners being made he was, however, soon relieved. He subsequently received the honour of Knighthood for his services, and a short time after the Peninsular war, accompanied his uncle, Gen. Sir James Leith, to Jaimaica, and there acted as a Military Secretary, and Quartermaster Adjutant-General. He returned home in 1830, after twenty-two years of a military life.

At this time politics ran high in France and Britain. Barricades had been erected on the streets of Paris, and a citizen King, Louis Philippe, placed upon the throne in room of a Bourbon. In England Parliamentary Reform had begun to occupy a large share of public attention, and we may suppose that, when Leith Hay was preparing his sketches of the Peninsular war for the press, he was also devoting his attention to politics, for in 1832, when the Reform Bill was passed, he came out as the Liberal candidate for the Elgin District of Burghs. He was not at home when canvassing began, but his friends were active : even some ladies in our little city were then most active for the Liberal candidate. He was opposed by by Mr holt M’Kenzie, who was son of the “Man of Feeling.” He was a formidable opponent- and excellent speaker, an admirable canvasser, ready to please every one. He was suspected to be a Conservative, from the principles of the noble family that sent him forwards, but ultimately turned out a Radical.

Mr Morison, now laird of Bognie, was another candidate , professing moderately Liberal principles. All three addressed the public, all three canvassed with might and main, and Elgin was agitated from the Witches’ Pot to the Hangman Ford. When the polling day came, and the result was known over the District of Burghs, 350 had voted for Sir Andrew, 227 for M’Kenzie, and 122 for Morrison. The rejoicing was unbounded. The successful candidate was carried through the town in a chair, the trades were out, flags were flying : it was a jubilee in Elgin, for the Liberal party had gained a great triumph.

Sir Andrew did not lose his popularity in the district by his conduct in the House of Commons. He was looked upon as a model member, paying great attention to local affairs, and always ready to assist young men who applied to him for situations. In 1834 he did much to get the Lossiemouth Harbour Bill passed, also, among other things, a Prison and Town House Bill for Forres and Elgin. In 1835 Parliament was dissolved, and there another contest for the Elgin Burghs. Sir Andrew was now opposed by Brodie of Brodie, who had great local influence, and whose character inspired confidence – giving him many friends and supporters. The great excitement of 1832 had died away, but the contest was keen. Sir Andrew polled 384, and Mr Brodie 264, this giving the successful candidate a majority of 120. In 1841 another Parliamentary election came round, and Sir Andrew this time found an opponent in Mr Duff of Haddo, in Banffshire. Mr Duff appeared as a Conservative, and had the whole influence of the Conservative families in the district. The contest was keen and close, for Sir Andrew maintained his seat only by a majority of 14, the numbers being 311 and 297.

The next Parliamentary Election occurred in 1847, and Sir Andrew had again, as in 1832, two opponents, the Hon. George Skene of Duff, and Mr Bannerman of Crimongate, now Sir Alexander Bannerman. The Liberal Party being thus split, the odds against Sir Andrew were now too powerful, for Mr Skene Duff polled 242 votes, while Sir Andrew polled 147, and Mr Bannerman 192, Sir Andrew thus losing hie seat by a majority of 95 votes.

These may be called the electioneering battles that Sir Andrew fought in his latter days. He was not long in Parliament after his first election till Lord Melbourne appointed him Clerk of the Ordnance, an office that brought him a considerable income, and which he filled during the years of 1834 an 1835. At a subsequent period he was also appointed to the Governorship of Bermuda, but did not go on to fill the situation. We may add that Sir Andrew contested the city of Aberdeen in 1852, and was unsuccessful.

The political career of the deceased was, in many respects, a brilliant one, for he was three times returned Member of Parliament for the Elgin Burghs in keenly contested elections. He was worthy of the honour of the constituency conferred upon him, for no Member of Parliament could have been more attentive to the welfare of the district he represented. Sir Andrew’s heart was in the right place, and his hand was ever ready to do a “good turn” to a deserving man. This made him more than respected, he was even beloved both by electors and non-electors, who were all proud of having such a representative in the House of Commons. He had no dislikes, partialities, or petty jealousies about him as a public servant, but had a generous nature, combined with a kindness, affability, and dignity of conduct that made his political opponents respect him almost as highly as his supporters. He was the same to both, often shaking those who opposed him heartily by the hand and saying, “I hope you will live to vote against me a second time.”

Though it be now fifteen years since he ceased to be our representative in Parliament, he never forgot Elgin, and up to his dying day, he was ready to “help and Elgin loon.” as he said, when it was in his power. As a member of Parliament, Sir Andrew stood high in the estimation of his fellow members in Scotland. When they resolved to banquet Lord Jeffrey, on the occasion of his being raised to the Bench, they unanimously chose Sir Andrew Leith Hay as Chairman – a circumstance which was justly considered a great compliment to the member of the Eligin Burghs.

But, we must say a word on the literary talents of the late Sir Andrew Leith Hay. Besides his work on the Peninsular War already noticed, he published a volume entitled, “The Castellated Architecture of Aberdeenshire,” in which he shows much antiquarian learning regarding his native county. He dressed up the dry bones of archaeology in a pleasant style, the natural liveliness and rich honour of the man always looking through the writer. Sir Andrew was an excellent public speaker, and admirably adapted for winning over public meetings to his opinions, and enlisting support in contested elections. He was ready, witty, and terse in his language, and, when he found amongst his most noisy opponents, those who were under personal obligations to him, he sometimes repaid their ingratitude with a withering remark, but accompanied with a smile. He was Liberal in his political opinions, but strongly denied being a Radical. He often said her would never desert the cause of the people, and he made good his words, both in and out of Parliament. In the House of Commons, he was not month the class of speakers that are indebted to courtesy for a hearing, but was, on the contrary, listened to with attention and respect, and, on questions pertaining to the army, he was looked upon as an authority, whose opinion deserved grave consideration.

As County Gentleman, Sir Andrew was highly respected. He took a deep interest in all that pertained to Aberdeenshire. He was Convenor of the County of Aberdeen, and devoted much time and attention to the county. He held this office till death, which will be deeply regretted, we are sure, by those among whom he laboured in setting the business of one of the largest counties in Scotland.

Sir Andrew married, in 1816, a daughter of the late William Clark, Esq. Of Buckland House, devon, and has survived her about three years. One of his sons died some months ago, at Haghland Farm, in the neighbourhood of Elgin. The eldest son, Colonel Leith Hay, succeeds to the property and honours of the family. Some of our readers will remember that we had occasion to mention honourably this gallant officer during the Crimean and Indian Wars, in both of which he distinguished himself. Like his now deceased father, he gained laurels in battle-fields. May he be as highly respected and esteemed in public and social life the qualities of head and heart that made us all admire Sir Andrew Leith Hay of Rannes.